The Debt to EBITA ratio may bring back nightmare memories of that financial accounting class you took in college. But it’s like eyebrow threading: it looks scarier than it is. The Debt to EBITDA ratio helps analysts compare a company’s debt amount (money borrowed) to money flowing in.

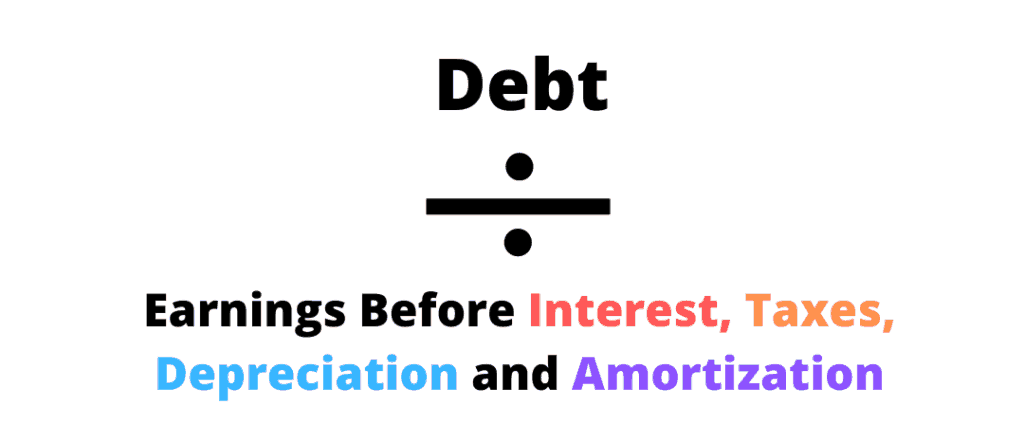

The formula is:

Debt-to-Ebitda Ratio: What is EBITA?

EBIT…duh what?

EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, and Depreciation, and Amortization.

Let’s break this down.

Interest: Money charged on debt payments. For a person, that’s like student loans or credit card interest. For a company, that’s like bonds, loans, revolving credit facilities, and other types of debt.

Taxes: Money paid to the government. Multi-national companies may owe taxes in more than one country

Depreciation: Think of depreciation as a slow faucet drip. Over time, certain assets’ values leak away. Like how the car you bought last year is worth 20% less. Things lose value either because they get old and worn out, or because the market values them less. Companies depreciate their inventory and machinery regularly, meaning their assets are worth less.

Amortization: Probs the trickiest one on here. At its simplest, amortization takes the cost of an asset and splitting up the payments into separate years. By assets, we are talking about things that exist purely on paper like patents, copyrights, trademarks, or franchise. We call these intangible assets.

When a company buys a trademark (or a celebrity trademarks an inane phrase) they amortize the cost over the number of years the trademark has value. So if they buy it for $20,000 and amortize it over 20 years, the “cost” per year is $1,000.

To bring amortization closer to home (literally), mortgages are also amortized. You pay a consistent monthly mortgage payment to reduce the total loan size you took out.

All of these expenses are not taken into consideration in EBITDA. EBITDA looks at a company’s income before subtracting any of these expenses.

Back to the Ratio

Solving for the ratio means dividing a company’s total debt by EBTIDA.

Debt includes all short-term and long-term debt payments.

Let’s say this great company called Dog-Cat Inc. has $3 million worth of debt and an EBTIDA of $1.5 billion.

$3 million / $1.5 million = 2

This number means that for every $1 of earnings Dog-Cat Inc. brings in, it has $2 of debt.

Now for the tougher questions: Is this a good ratio number or a bad one?

The answer, like most things in financial analysis, is that it depends. In some industries that are more capital-intense (read: need a lot of cash money to keep things running), a higher Debt to EBITDA ratio might make sense. In others, a high ratio could be a big red flag.

For example, General Motors’s (GM) debt-to-EBITDA ratio at the end of 2019 was 5.17. Ford Motor Company’s (F) debt-to-EBIDTA ratio at the end of 2019 was 17.18. Based on that alone, which company would we rather own?

These numbers are just one puzzle piece in a greater financial picture, but they can tell you something about a company’s financial fitness, just like our individual credit scores tell lenders something about us.

Most times, just like we as people feel better owning less debt, we like companies that have small debt-to-EBITDA ratios. Shows fiscal responsibility and all that. Earned money is better than borrowed money. However, there are times when it makes sense for a company to take on more debt. Like if it’s trying to grow quickly. Or interest rates (cost of borrowing) are super low.

Again, it depends. #annoyingbuttrue

When using debt-to-EBITDA ratios to analyze a potential stock purchase, also consider the company’s:

- Growth Potential

- Type of debt (long vs short-term)

- Debt to assets ratio

Net Debt to EBITDA

You might see some people refer to a “net debt to EBITDA” ratio. All this means is they took the total debt and subtracted out cash.

As a person, your net debt is all your debts (student loans, credit cards, auto payments, mortgage) minus all the cash or cash-equivalents you have. Cash-equivalents mean things that aren’t cash now, but can quickly be turned into cash, like a treasury bond or a very liquid stock holding.

If you have more cash than debt, your net debt will be a negative number. IRL example: you have $30,000 in the bank and $2,000 in student loans. Your net debt is $2,000 – $30,000 = -$28,000. People who just signed mortgages will not relate to this feeling.

For companies, it works a bit differently. They keep less cash on hand and put more money towards expenses, assets, or inventory. So net debt is usually positive.

Net Debt-to-EBITDA shows how long it would take a company to pay back its debt if it threw all its cash at the problem. If a company has a ton of debt but also a ton of cash, the debt might not be such a big deal.

Let’s explore this with Dog-Cat Inc. We already determined it has a debt-to-EBITDA ratio of 2. In addition to $3 million in debt and $1.5 million in EBITDA, it has $1 million in cash. Here’s the calculation for net debt-to-EBITDA:

(3 mil – 1 mil) / 1.5 mil = 1.33

For every $1.33 of net debt, Dog-Cat Inc. has $1 of EBITDA.

RECAP

- Debt-to-EBITDA: A ratio that shows a company’s ability to pay off debt, ignoring expenses of interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization

- Quick way to assess a company’s debt load and financial health

- A high ratio means more money is being borrowed than taken in – aka not ideal